|

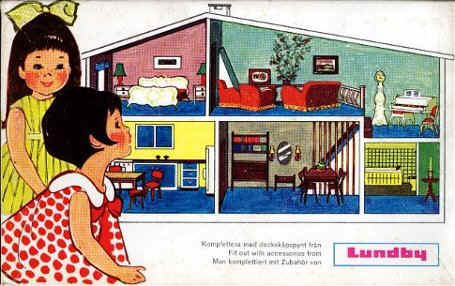

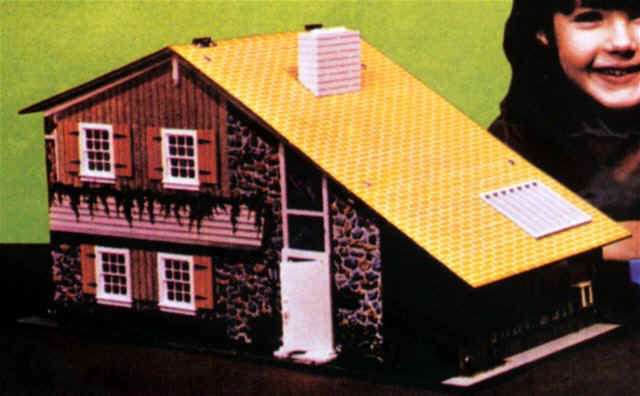

THE LUNDBY GOTHENBURG DOLLHOUSE ITS EVOLUTION AND SURVIVAL FROM “MODERN” TO “TRADITIONAL”

by Jennifer McKendry ©

|

|

ROOF FORM On the whole, dollhouses until the

1950s were constructed w

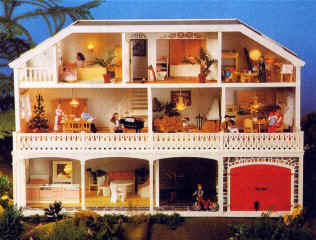

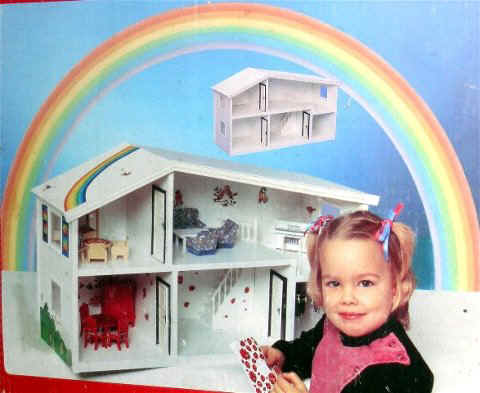

Rainbow House in pink with original furniture, 1985

DOCUMENTED SOURCES

Unfortunately, there is little printed visual evidence that has survived from

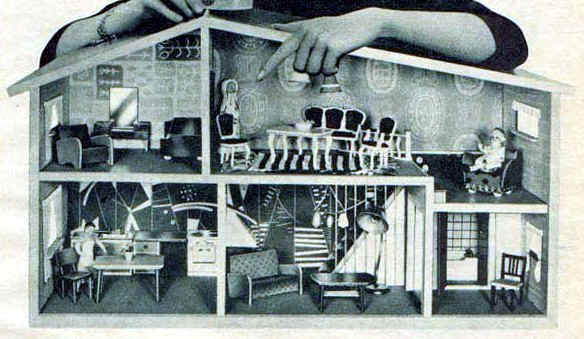

the 1950s of Lundby products. The earliest

web-published catalogue of AB Lundby Leksaksfabrik, likely from the late 1950s (previously

thought to be 1947), shows a house with a traditional gable roof over

two-storey box-l

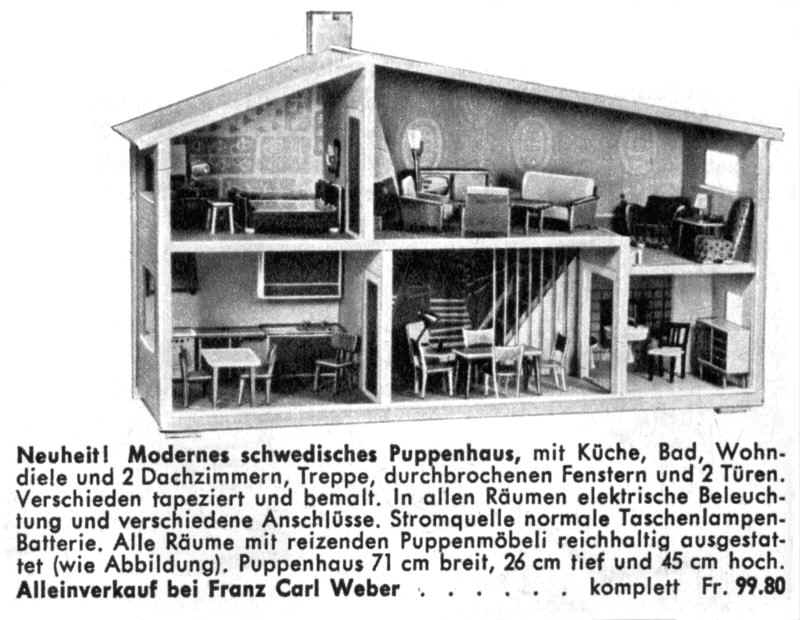

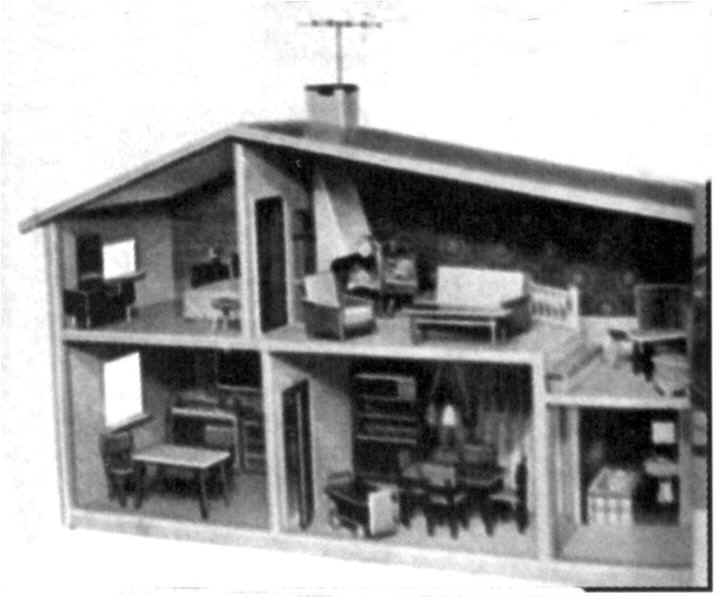

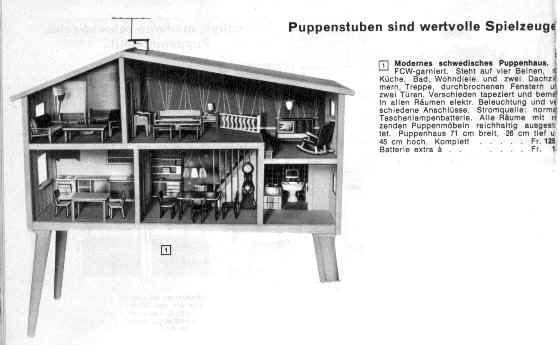

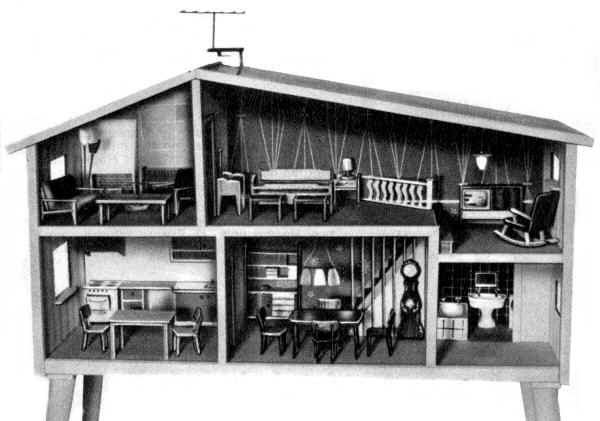

Recently a number of “Modernes schwedisches Puppenhaus…” (Modern Swedish dollhouse) illustrations from 1960 to 1964 have surfaced. For 1960 there are 2 views of the same house, although with different furnishings and variations in the wallpaper: the first illustration below is from an advertisement of 1960 for Fenom (kindly sent by a Lundby collector) and the second from Franz Carl Weber's catalogue which, fortunately shows the chimney. The dining-room wallpaper is spectacularly modern with a bold abstract image. The Weber ad emphasizes "Neuhuit!" -- does this mean a new addition to the products sold by Weber or is the form of the house new? The answer willl materialize if dated images from the 1950s are discovered.

two houses from 1960

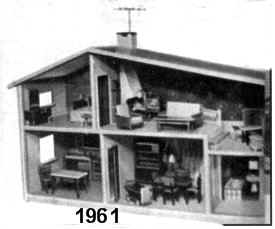

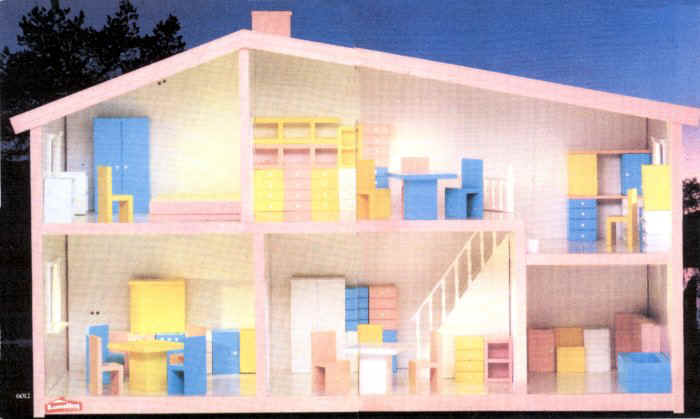

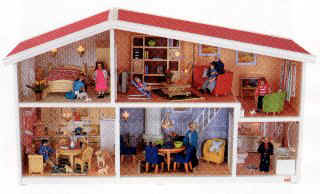

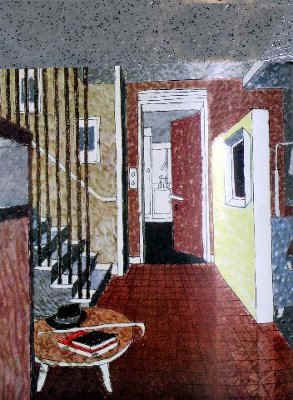

below From the Weber catalogue of 1961-62: Weber’s caption, which begins, “Modernes schwedisches Puppenhaus…” (Modern Swedish dollhouse). The caption goes on to note that it was completely papered and painted, held many charming pieces of furniture and was safely wired for electricity. The dollhouse was 71 cm wide, 26 cm deep and 45 cm high. These measurements are about the same as a Gothenburg House from the mid 1970s, except it is a little lower because, by then, it no longer incorporated the television antenna that topped the 1961 house behind the chimney. It is worth noting that the chimney cap has a lower open part in the top centre, characteristic of Lundby houses in the 1960s and first half of the 1970s. Aside from the confirmation, via the antenna, that a television was part of the 1961 furnishings, other pieces appear to be in a simple “modern” style. The independent fireplace with its white slanted upper part is familiar because it was carried in the Lundby line until 1975 (catalogue number 5773). The interior plan of 1961 is familiar including the balustrade protecting the stair-well in the large upstairs room (furnished as a sitting room with fireplace) with its open modern form that includes a lower portion (sort of an extensive stair landing) accessed by a single long step. The staircase descending into the centre main-floor room (furnished as a dining room) is distinguished by floor-to-ceiling wood rectangular spindles, seen in real houses of this period (for example, as illustrated in the Architectural Review of November 1950, A), and surviving in Lundby houses (B: example from the 1960s; C: rendering from a box pre-1967) to at least 1972 . By 1974 (and still in use today), they were replaced by less “dated” white, turned uprights under a hand-railing.

A B

The 1961 bedroom, kitchen and

bathroom were in their familiar locations. The bathroom with its “built-in”

tub and pedestal sink had a wide opening off the dining room - probably the

same arrangement seen in the 1966 catalogue. This seems odd design concerning

privacy but it was likely that the area at the front of the bathroom was

meant to represent a hall with an imaginary wall and door separating the

bathroom proper. In 1967, one could purchase a sauna to place in this front

portion of the bathroom. By 1970, Lundby introduced

a

(right; sink with counter, 1967-70; tub and toilet, 1967-77; shower, 1974-77.)

1963-64 Franz Carl Weber catalogue: note the 4 legs (of equal length - cropped in photograph) and TV antenna; close view below

1963-64 Weber catalogue showing "Lundby modern Swedish dollhouse furniture"; some of the lighting fixtures and lamps are shown in the house illustrated above -- but any would be suitable to use in a Lundby house of this era.

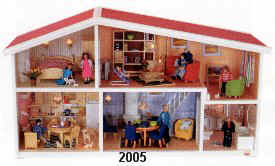

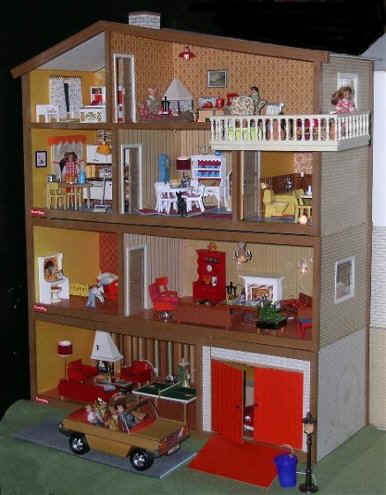

About this time, it was optimistically described as a "modern villa", but – perhaps as an acknowledgement of its increasingly dated form (novel in the 1950s) – there was an ongoing attempt to create variety with optional additions (left, c1975-78). Despite spicing up the design by adding a storey with a “built-in” garage designed for a special Lundby car in 1974 and, a year later, a balcony and garden, the house was described realistically in 1981 as Lundby’s “traditional dollhouse.” Even changing in 1979 from the brown trim to white was not enough to modernize it. By 1999, enough time had passed to wax sentimental about its history and the Lundby Home Journal compared the 1967 version with one from 1975. As part of the promotional material, there was a consistent reminder given to customers that the furnishings were continuously updated and that the wiring system was an advantage. Although the company today promotes the idea that Lundby was the first company in the world to manufacture dollhouses wired for electricity, other companies, such as the Vista Toy Company of New York or Schoenhut of Philadelphia, had electric lights since at least the mid 1930s. It is likely true that Lundby is one of the oldest companies still making mass-produced dollhouses famous for their built-in wiring.

************************* Why then did the Gothenburg House survive the vicissitudes of changing taste? I think it was a clever blend of the traditional and modern. How could it become “dated” if it was intrinsically traditional?

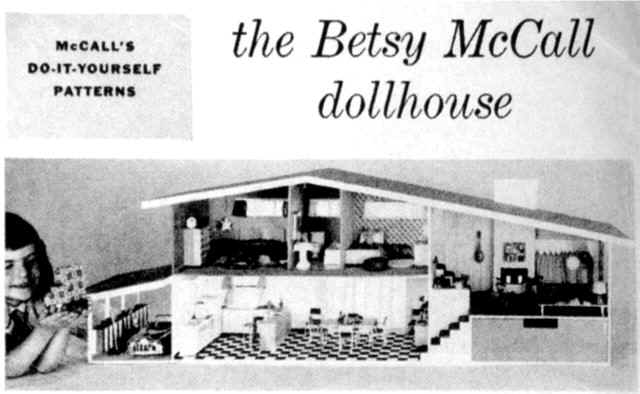

SWEDISH MODERN IN ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN Since 1930, Swedish architecture has been admired for its Modern style, a movement slowed down and impeded by the Second World War. A love of “Scandinavian Design” (a catch phrase in the 1967 Lundby catalogue) in the decorative arts swept through North America in the late 1950s and 1960s with products imported from Norway, Finland, Denmark and Sweden. From 1953 to 1957, for example, an exhibition, “Design in Scandinavia” travelled throughout North America with 700 examples of decorative arts from Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. In architecture, it is difficult to

separate national styles in the late 1940s and 1950s, because the

improvements in communications through illustrated magazines and books, as

well as the immigration to the United States of avant-garde European

architects (such as Walter Gropius and Mies van der

Rohe), meant the quick spread of ideas resulting in

the “International Style.” Favouring functionalism, it rejected historical

decorations and forms and celebrated new building materials such as steel,

reinforced concrete and plate glass. The lack of fussy ornament and simple

lines of the Gothenburg House align it with the modern movement. American dollhouse manufacturers were producing houses with the asymmetrical roofline in the 1950s. By 1956, you could even build your own house from patterns provided by a McCall’s iron-on pattern to create a split-level under an asymmetrical roof with an attached carport (left). Or a Terry Lynn dollhouse in “California Modern” of 1953. It would be interesting to know if Lundby took the Gothenburg form from other manufacturers or the reverse is true. Until more documentation in the form of written descriptions or illustrations from the early 1950s appears, it is impossible to know. Generally speaking, dollhouse manufacturers reflect what is popular in the real world. Children want to manipulate houses, interiors and furnishings that echo those controlled by their parents. The basic form of the Gothenburg House was part of the modern style appearing in North American and European suburbs in the 1950s. About 1952, in a development at Don Mills (now part of Toronto, Ontario, Canada), houses were being designed by architects who were influenced by Swedish Modern and indirectly by the ideas of the German Bauhaus (an avant-garde school of art and design that flourished from 1919 to 1933) via the work of Walter Gropius. A photograph in the Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC), January 1954 shows new Don Mills houses with the Lundby Gothenburg roof form (below). Other examples include houses in the Philadelphia-Wilmington area, as illustrated in the Practical Builder in August 1956 (below left). In other words, it was mainstream by the mid 1950s. In 1958, a number of houses (below right) of this type was built in Utby, Gothenburg, to the designs of Yngve Lundquist under the impetus of a periodical Hem I Sverige (Homes in Sweden).

above: Don Mills, Ontario, 1952-54

below left: Philadelphia-Wilmington, 1956 below right: Gothenburg, 1958

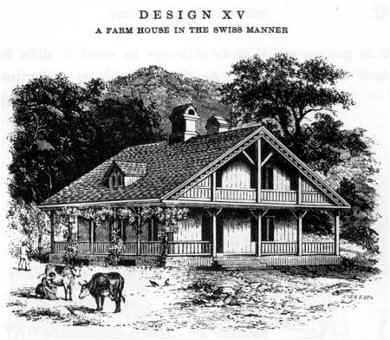

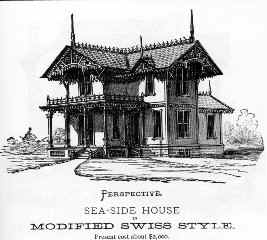

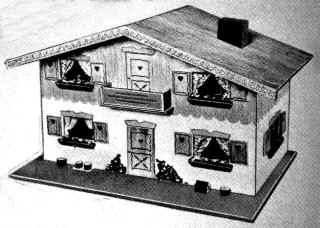

THE CHALET Despite interpreting the Gothenburg

House as “modern,” there may also be an allegiance to a traditional European

house type – the chalet, which is particularly well represented by the Swiss

chalet. This was well known as a type even in 19th -century United

States. A.J. Downing, a popular American writer on architecture, illustrates

an example

The chalet relationship to certain

dollhouses of the mid 20th century is

demonstrated

Regardless of the permeations of style, one can argue that there was a familiar comfort to the Gothenburg House despite its modernity. ************************ While the Lundby Gothenburg House may not have originated the roof form associated with it, it is remarkable that it has survived over such a long period of time. It modern aspects, novel in the 1950s, became “traditional” in the 1980s. Its survival may have occurred because it merged modern into customary. We can let George Swinton – when reviewing in 1954 the travelling exhibition on Scandinavian design in the Journal of the RAIC – have the last word: It is, of course, the interrelationship of age-old craft knowledge, continuous tradition, which is the knowledge and use of indigenous historical forms and the individual creative mind, which have brought about the refinement of Scandinavian objects for daily use….the form does not merely follow the function, the function derives its life from the form. top of page home page lights in dollhouses 1890 to 1990 including Lundby history of dollhouses & furnishings from 1890-1990 including Lundby |